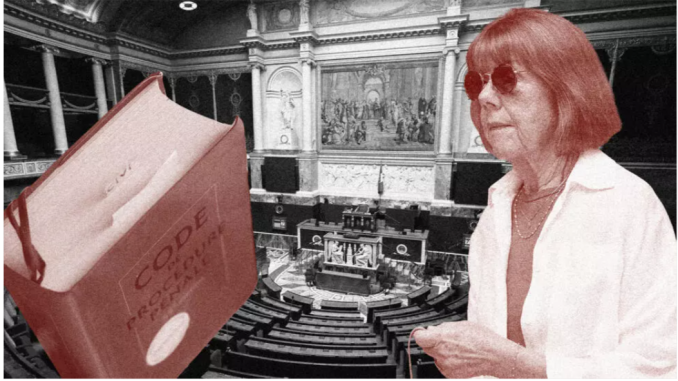

Gisèle Pelicot stands at the bar, facing Judge Roger Arata. “Did you consent to the choice of one of these partners?” asks the president of the Vaucluse criminal court. “The term partner deeply shocks me (…) Once again, in the state I was in, I was not able to answer, I was in a coma,” replies the septuagenarian, quite annoyed by the magistrate’s questions.

The scene takes place at the end of September in the Avignon court, in the middle of the Mazan rape trial. Dominique Pelicot, 71, and 50 other defendants are on trial for sexually abusing Gisèle Pelicot while she was drugged and asleep. Since it opened on September 2, the trial has been making headlines due to the scale of the facts, its international media coverage, but also because of the questions it raises about the judicial treatment of sexual violence in France.

At the heart of the debates on the characterization of rape, all the accused deny intentionality: yes, they had sexual intercourse with Gisèle Pelicot. No, they did not “know” that she did not consent. “The fact that the defense lawyers are rushing into the gap that exists on the fact that there is no notion of consent in the criminal definition of rape demonstrates the impact of this flaw,” believes Mélanie Vogel, Green senator for French people abroad. In 2023, the elected official was at the origin of a bill, not adopted, recognizing the absence of consent as a constituent element of sexual assault and rape.

A limited legal definition

Unlike Canada since 1992 , Sweden , or its European neighbors, France does not mention consent in its criminal definition of rape. Article 222-23 of the penal code defines it as “any act of sexual penetration, of whatever nature, or any oral-genital act committed on the person of another by violence, constraint, threat or surprise is rape.” In other words, “magistrates have the obligation to prove one of these four elements. If they fail to do so, there is no possible conviction for rape,” summarizes Catherine Le Magueresse, lawyer and associate researcher at the Institute of Legal and Philosophical Sciences at the Sorbonne.

magistrates have the obligation to prove one of these four elements. If they fail to do so, there is no possible conviction for rape,” summarizes Catherine Le Magueresse, lawyer and associate researcher at the Institute of Legal and Philosophical Sciences at the Sorbonne.

Although France ratified the Istanbul Convention in 2014 , which requires signatory states to include the notion of consent in their legal definition of rape, it has since been noted for its opposition to the issue. In March 2022, it was one of the few countries, along with Germany and Hungary , to vote against the inclusion of rape in the European directive to combat violence against women. “It is partly because of France that European women do not have a definition of rape in a directive that deals with sexual violence, which is quite mind-boggling,” denounces lawyer Catherine Le Magueresse, who published “Les pièges du connaître” (Ixe editions, 2021).

Long opposed to this legislative change, Emmanuel Macron ‘s government made an about-face at the end of September, in the middle of the Mazan rape trial. In an interview with France Inter , Justice Minister Didier Migaud said he was in favor of introducing consent into the French penal code. Launched in December 2023, then interrupted by the dissolution of the National Assembly , a fact-finding mission “on the criminal definition of rape” is due to resume its work in November with a view to producing a report in early 2025. “The way rape is judged today is not satisfactory with regard to victims. It does not do enough to protect them,” believes Véronique Riotton, Ensemble pour la République MP for Haute-Savoie and former chair-rapporteur of the parliamentary mission.

A highly inflammatory debate

Despite this encouragement from the Minister of Justice, the issue of consent continues to cause tension in the French political and judicial world. “Is it the role of criminal law to define the consent of a victim, instead of focusing on defining the criminal’s responsibility?”, asked the former Minister of Justice, Éric Dupond-Moretti, last February. “The only person responsible is the rapist. The major risk is to place the burden of proof of consent on the victim.”

Some women’s rights associations are also opposed to it, such as the Collectif féministe contre le viol. For its president, Emmanuelle Piet, asking the question of consent amounts to “looking away from the victim when we should be questioning the aggressor’s strategy. A rapist is someone who gets off on destroying, it has nothing to do with sexuality.” “The consequence of this drift is well known: the victim’s attitude is examined in the smallest details. The words she said, or not, the way she acted, or not,” denounced a collective of associations opposed to the introduction of consent in an October column .

Others, such as psychiatrist and legal expert Paul Bensussan, are concerned about the risk of contractualization of sexual relations that would be implied by the inclusion of consent in the penal code: “Can we really contractualize emotions, and how can we fluidly ‘withdraw’ consent given at a specific moment, if things go badly?”, he worried in an article published in early 2024 in Le Point .

More measured, the magistrates’ union leans “rather in favour” of including consent in the penal code but warns. “Once we have accepted the notion of consent, there is another difficulty, which is the risk of finding the same pitfalls as with the four current criteria [violence, surprise, constraint, threat, editor’s note], which are also very subjective and whose interpretation can be guided by the sexist representations of magistrates,” explains Nelly Bertrand, the union’s general secretary.

Feminist associations systematically point out that 94% of rape investigations end up being closed in France, according to a study by the Institute of Public Policy , compared to 85% for other personal assaults. But according to Nelly Bertrand, “the introduction of consent alone would not change much in practice. There is real work to be done on the methods of investigation in rape cases, in other words on the search for proof, in order to overcome the supposedly insurmountable ‘one’s word against another’s word’ and thus the massive rate of cases being closed without follow-up”. “For the Mazan case, the police conducted a magnificent investigation, but we see that many investigators still refuse to take complaints. We need to focus on training police officers and magistrates and stop discrediting the victims’ words”, adds Emmanuelle Piet, president of the Collectif féministe contre le viol.

“Free and informed” consent

Former chair of the parliamentary mission, MP Véronique Riotton knows that she is walking on eggshells: “We have warnings from everywhere. As soon as we write something, we are going to be attacked,” sums up the one who was received last week by the Minister of Justice. “The minister reaffirms his support for our work and at the same time his vigilance to write [the law] in the fairest way. We are going to touch the penal code, so let’s be frugal!”, she insists.

To avoid controversy, lawyer Catherine Le Magueresse argues for defining consent as “a free (without any coercion) and informed agreement. If the person says nothing, they are not saying ‘yes’, so there is no consent. Silence no longer consents. If the person says ‘no’, that means ‘no’. This shuts down the excuse that says that the no was not serious. Concerning people who say ‘yes’, but under duress, we consider that it is not valid, because it is not free or informed.”

The lawyer cites the case of Sweden, where the introduction of consent into the penal code had sparked the same controversies as in France. Adopted by Parliament in May 2018, the text establishes that any sexual act performed without the other having participated “freely” is rape. As a result, convictions for rape increased by 75% between 2017 and 2019, according to the National Council for Crime Prevention (Brå). “Investigations are more thorough and complaints are filed less quickly,” rejoiced a Swedish lawyer in the columns of Le Monde . “Of course, convictions are important,” reacts Catherine Le Magueresse. “But the law also has an educational function, it would show that we want to change sexual relations between men and women, that we are concerned about the reciprocity of desires.”

Alignment of the planets

For Senator Mélanie Vogel, this change in the law would in any case be in the direction of progress: “The penal code defines what a society considers good or bad. By introducing the notion of consent, we would reverse our relationship with the body of others by considering that it is unavailable as long as this person does not agree.”

Leave a Reply